Originally published in Vol 3. Issue 1 of Midas Magazine, Fall 2022

Why We Take Photos

Why We Take Photos

Written and photographed by Claire Hambrick, featuring an interview with Wendy Hernandez Lopez. Originally Published December 2022

A photograph tells as much about the person behind the camera as it does about who’s in front — if you pay attention. I’ve long found photography to be the one expression of any creative pursuit that resonates with me more than anything else. And I’ve tried a lot — writing, acting, music, painting, etc, but nothing gives me the agency that photography does. It’s empowering to capture images you deem worthy of being remembered and shared. If all art is a matter of connecting, photography allows me to share with others my experience and perception of the people and world around me. My love for sharing images and constructing life into a visible, tangible item is why Midas Magazine exists at all.

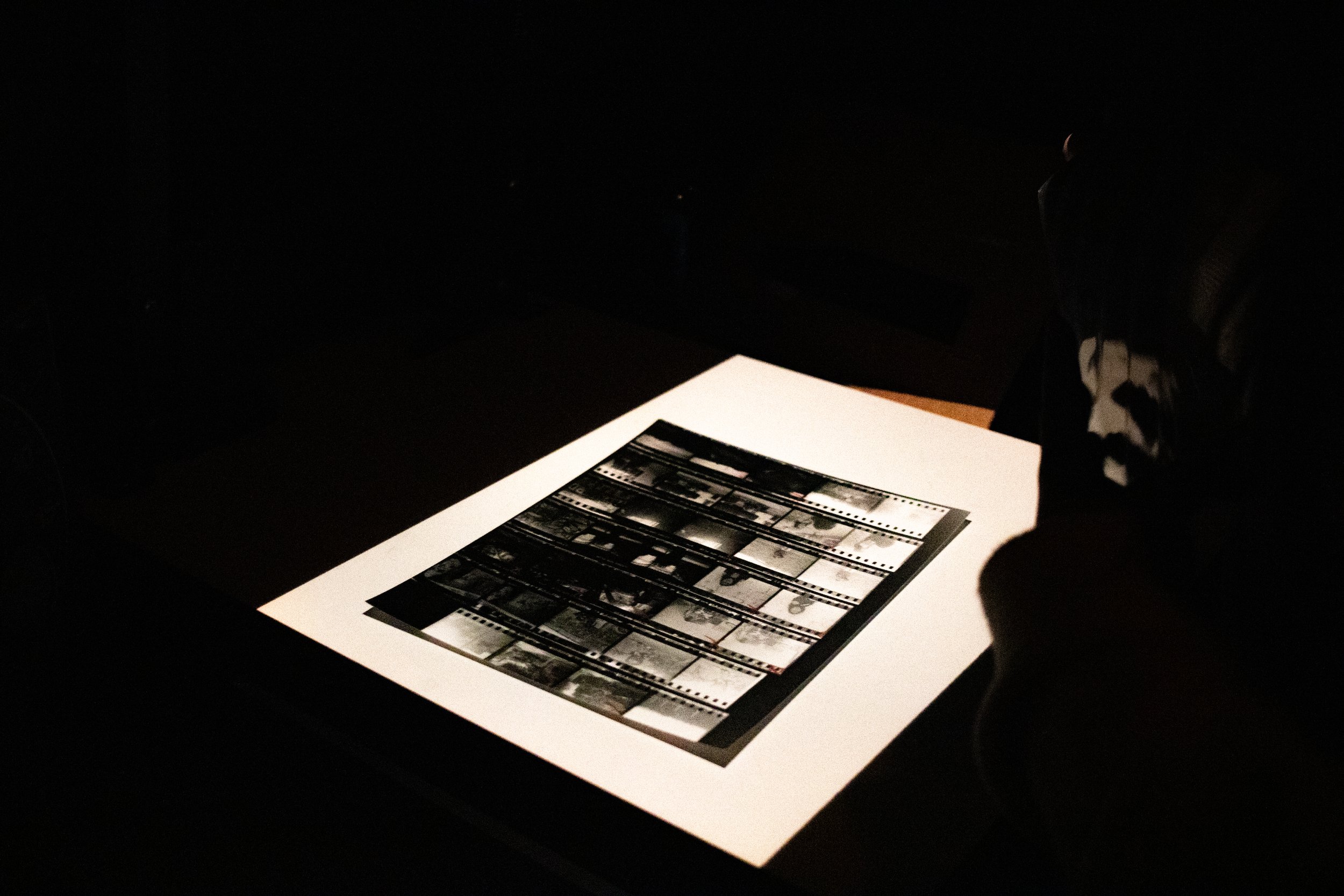

Besides, what's more nostalgic than a photograph? Old photos of the past let us bridge gaps of time and distance. It’s proof that a world beyond the current one existed, that the names in your family tree aren’t just ghosts but were real people; whether it's the person in the frame or merely the fact that the person behind the camera decided this moment in time was worth preserving, unknowingly giving us something to hold on to and form theories about decades later. It’s the same reason I find so much joy in witnessing more and more people my age take film photos. The physical nature of film and print photos, which in most contexts have become extinct out of our desire for digital postable photos, lets us document the present to give the future a past to hold on to.

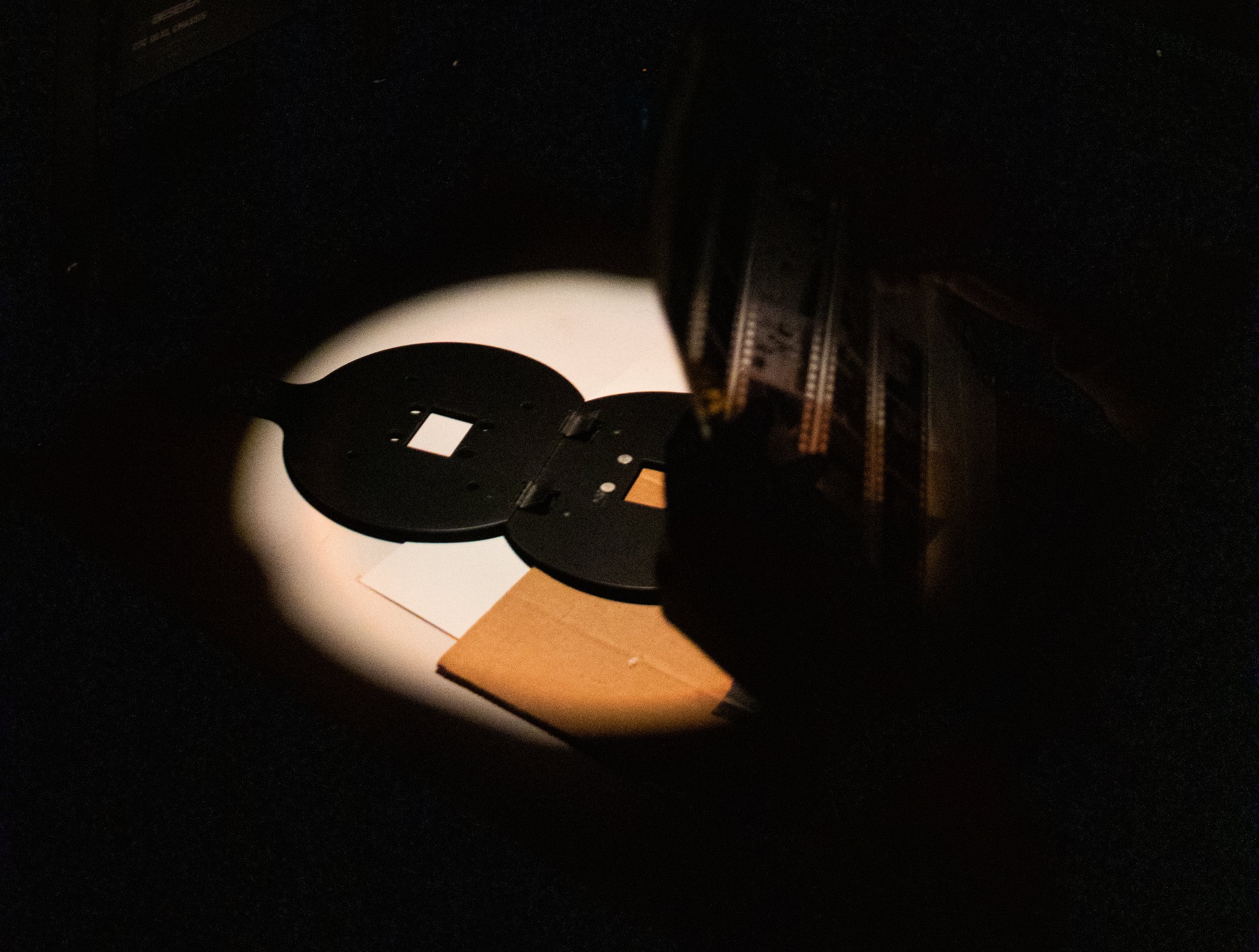

The return to analog photography in younger generations is nothing new, though it is pretty illogical. It's slow, expensive, easy to mess up, and unforgiving. Our phone cameras allow us to take unlimited, high-quality photos in the blink of an eye. And, yet, something about film photography persists. We see it in the trend of disposable cameras popping up more in high schools, college parties, and celebrity Instagrams, as well as in mainstream media, with HBO’s Euphoria shooting its culture-shifting season two entirely on Kodak Ektachrome film. There’s something delightfully nostalgic about the medium that makes it worthy of our time and money even if it is antithetical to our normal expectation of ease and immediacy. If anything, the ritual of converting an image to a negative, editing, enlarging, fixing grain, cropping, uploading, or printing, is the very thing that makes it so special and resilient.

If we think about shooting film as a way to document the future’s history, it makes it even more important to value the perspective of the photographer. One of my favorite quotes on this subject is by the late photo curator, John Szarkowski, who said that “one could compare the art of photography with the act of pointing.” Photography is a matter of turning our attention to something. It can be an act of love or an act of rebellion by fighting against our societal understanding of who has the power and authority to tell stories. One of the easiest ways to understand a culture at any given place or time is by looking at its media, TV, and movies. Since these feats typically require lots of money and access, anyone without those forms of power is often excluded from having their truth told authentically. Recording your history is crucial so that no one else can speak for you or over you.

This semester, I met a new photographer who uses film to document her culture and community. I asked Wendy Hernandez Lopez to work on a photoshoot for Midas to accompany Jasmine Palacio’s written piece at the beginning of this issue. During the process, I got to know Wendy and her inspirations. We sat down for a conversation before the shoot to talk about photography, nostalgia, and the importance of documenting your history.

Claire Hambrick: Why did you get into photography?

Wendy Hernandez Lopez: I’ve always had a weird interest in film ever since I was a younger girl and I think that’s because of my grandfather. My grandfather worked for a big TV studio in Mexico City. He was always in the background of major things. In Mexico, everyone knows El Chavo del Ocho. That was such a cool thing to me, that my grandfather was the guy who filmed these episodes. He wasn’t the one acting but he made history with a camera. I’ve always been a visual person; even when I count, I have to put my fingers out, because I’m not as good at thinking just in my head. So knowing that he could make history with a video or picture was just crazy to me.

CH: What was your first experience with shooting on film? Did it go how you planned?

WHL: My first roll was based on just different Mexican markets here in Charlotte. I did interviews about what the community is like and what markets show up on the East side of Charlotte, where I live. There’s a lot of cultural markets: we have bakeries, quinceañera stores, and meat shops, so I took pictures there. I documented those, but none of those photos came out (laughs). I think that motivated me to keep going because I was just left with the want to see the photos finally come out.

CH: It’s one of the best and worst things about shooting on film. Everyone is bound to mess up a roll of film at least once and the first time can always be a little heartbreaking, especially when you have so much anticipation to see how the images will come out. What about film specifically appeals to you as a photographer instead of easier, digital methods of capturing images?

WHL: The process is so exciting! You don’t get to see the pictures you’ve taken. Right now in this generation, myself included, we’re used to having everything in our hands in the moment, in the blink of an eye. You learn patience with film photography because you don’t have that luxury. It just makes it so much more fun. It’s kind of like a little mystery; are you going to get the perfect picture or not? And you may have something in mind. Like right now, I’m envisioning this photoshoot going smoothly. I have a mood board, and I have inspiration, but there's always that chance that it's not going to turn out anything like you thought. [This interview occurred right before hurricane Ian hit Charlotte, the day of the scheduled shoot.]

CH: What kind of pictures are you drawn to taking?

WHL: I think most of my photography has been based on my identity and my culture. It’s just something that my parents have always inculcated into my family. I know some people get embarrassed or are not proud of saying where they’re from, but on the other hand — my parents never really gave me a choice to not be proud. I think it’s so cool.

Photos are a big part of my culture in general. We love to remember the past, we have a whole holiday on it. We put up altars in October with pictures of our loved ones on them. It’s so peaceful to have a nostalgic moment and relive something that you used to love or had good memories with. Pictures have always been a big thing in any immigrant’s life, though I can only speak for my own. It’s a little bit of what we have from across the border, especially for those of us who can’t go often or can’t go at all. So to capture a moment in a little frame is so special.

Why We Take Photos in Vol 3. Issue 1 of Midas Magazine

Designed by Aily Valencia Cervantes

Editor-in-Chief: Krishma Indrasanan

Managing Editor: Sanura Ezeagu